We all know the wage gap between men and women is there, but the cause of that divide? It's not so easy. And now, thanks to a new study, there's another possibility to consider: a motherhood penalty.

In a study released earlier this year, Henrik Kleven, an economist at Princeton, turned his attention to Denmark—a country that offers a full year's paid family leave to both mothers and fathers among other social programs (including public childcare). All these elements suggest that the motherhood gap shouldn't affect Danish women to the same degree that it does American women, where there's no guaranteed leave for mothers.

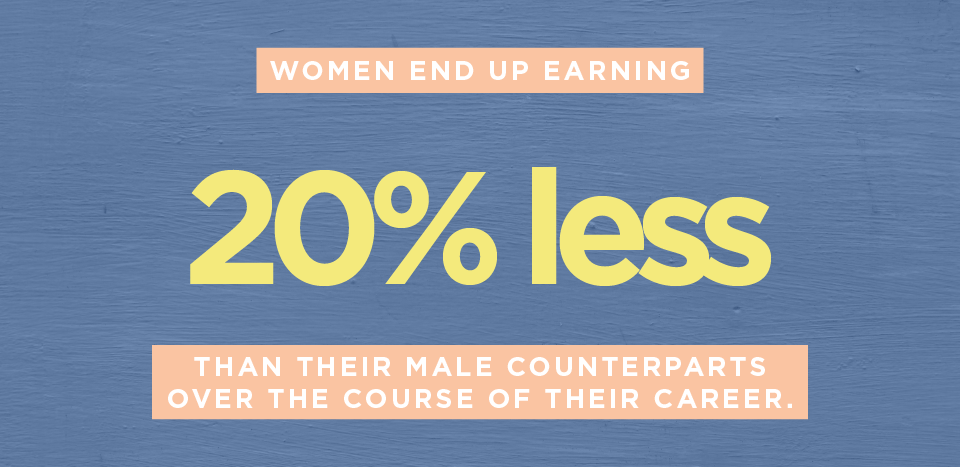

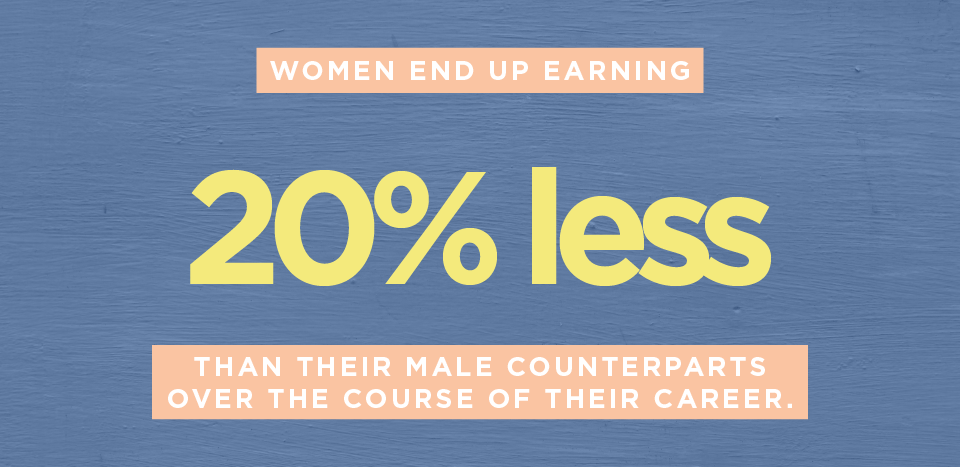

And yet, according to an article in Vox, Kleven found "a sharp decline in women’s earnings after the birth of their first child—with no comparable salary drop for men. The cumulative effect is huge: Women end up earning 20 percent less than their male counterparts over the course of their career." The study goes on to estimate that childbearing accounts for 80 percent of the wage gap in Denmark.

But there's something more interesting about the study beyond the unfair wage gap—something that implies that the issue is cultural as much as it is monetary. Kleven reported that fathers in his study don't experience the same wage gap as mothers—in fact, having children doesn't negatively affect their salaries at all. That's not all that surprising given the fact that

The New York Times recently reported that while there's a motherhood penalty, men experience a "

fatherhood bonus." Why?

Kleven's study found that women tend to take more of the Denmark-sponsored leave even though it could be used by either parent—which implies that women are expected (or feel they should) take on more of the responsibilities at home after having a child. But beyond that, Vox explains, "Public opinion data that Kleven cites shows, for example, that most Danish adults (and American adults, for that matter) believe that women with young children should not hold full-time jobs."

So even if a woman did choose to split the leave 50-50 or even plan to let her husband take more of the leave, it might still negatively affect her opportunities at work.

It's Not Just About The Money

Other studies have found the motherhood penalty goes much deeper than salary discrepancies—in Denmark or America. A recent

Fast Company article, "

Even Women Who Earn More Money Still Do Most of the Work at Home," argues that after the day is done, women are expected to take on more duties during their "second shift" than men. Says Fast Company:

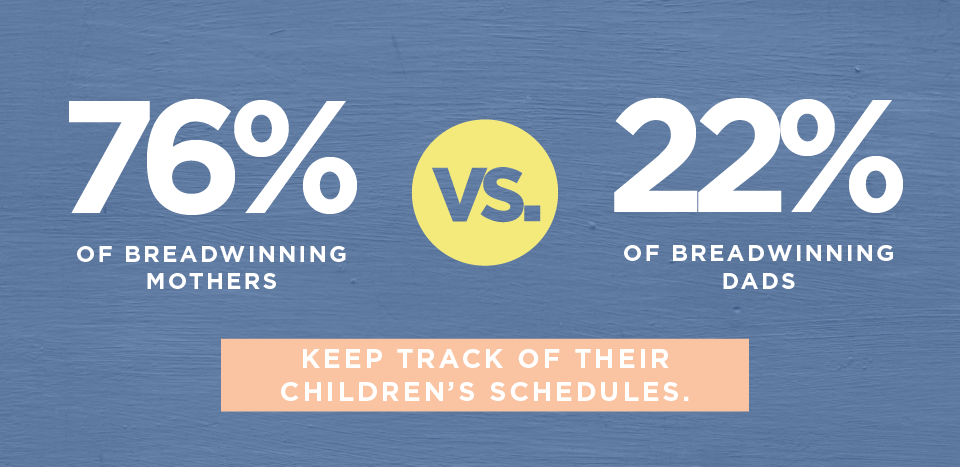

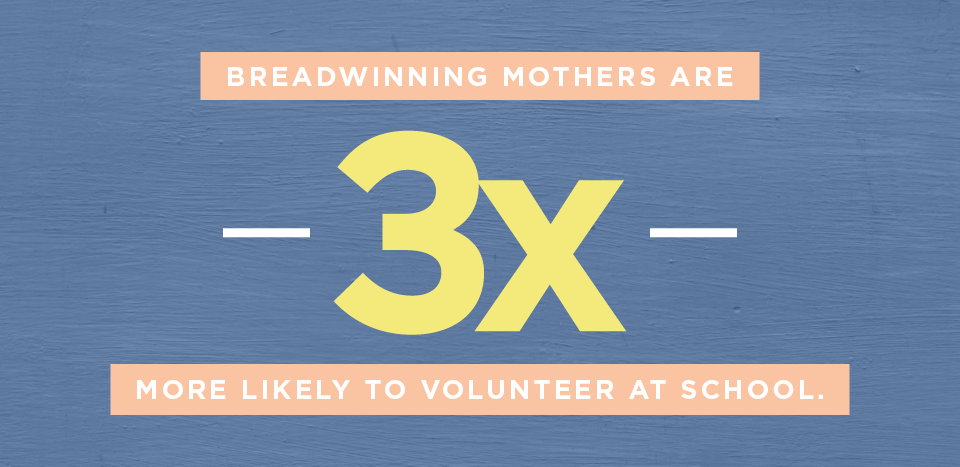

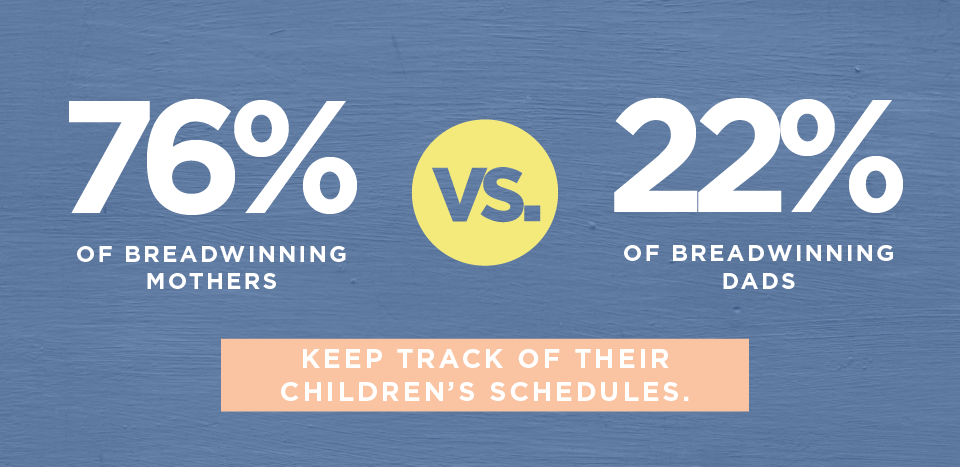

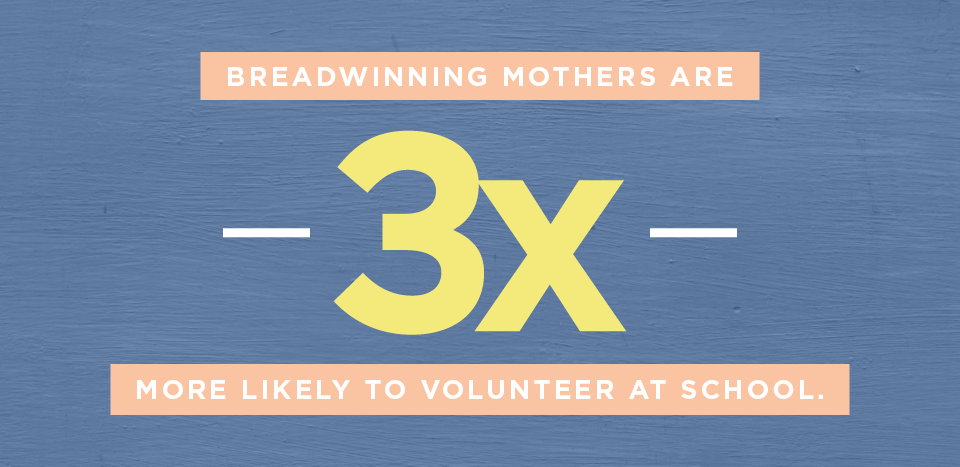

The Modern Family Index polled 2,082 American workers with at least one child under the age of 18, which revealed that among those shouldering the bulk of support with their salary, 76% of breadwinning mothers are keeping track of their children’s schedules vs. 22% of breadwinning dads. They are also three times more likely to volunteer at school (63% vs. 19%) and nearly twice as likely to make sure all family responsibilities are handled (71% vs. 38%)."

Anyone who's raising children while also building a career—or anyone who had a mother who also juggled a career—knows that the workday doesn't end when you leave the office. Cultural norms expect women to shoulder more of the work at home, and studies are finding that it's a recipe for burnout. "While these working moms juggle family responsibilities, they also claim to be fulfilled by their careers," explains Fast Company, but they also cite some pretty dire statistics:

- 69% of working moms say their responsibilities create a mental load

- 52% are burning out from the weight of their household responsibilities

So What Do We Do?

When the motherhood penalty isn't just about taking time off but about how women spend (and are expected to spend) their time, how can we make it easier for mothers to avoid burnout and narrow the wage gap they're facing?

Vox points to policy changes. "Countries have the ability to shape what child-rearing looks like with how they structure parental leave policies, for example. Outside of Denmark, most other Scandinavian countries have decided it is a societal good to encourage men to take time off after the birth of their child—and assigned a set amount of leave just for fathers."

Then there are company policies. Offering benefits like flexible schedules and post-maternity leave policies (because getting back into work is often more difficult than the work itself) can mean more opportunities for growth for women long-term. It's one of the main reasons why

we profile companies that offer those sorts of benefits.

But there are also ways to shift perspective on a couple-by-couple basis, meaning that if you're talking about having children with your partner or already have them, thinking about how you'll divide the work is essential to your career potential.

In a New York Times piece on the motherhood gap, Sari Kerr an economist at Wellesley College argues that we need to stop ourselves from choosing the "easy" option:

"It is logical for couples to decide that the person who earns less, usually a woman, does more of the household chores and child care, Ms. Kerr said. But it’s also a reason women earn less in the first place. 'That reinforces the pay gap in the labor market, and we’re trapped in this self-reinforcing cycle,' she said."

In the end, breaking the cycle might need to happen one policy shift, company benefit, and conversation between parents at a time.