This article by Sarah Goff-Dupont originally appeared in Work Life by Atlassian. It is republished with permission.

Great leaders are often thought of as people who made perfect decisions. Who saw every curve-ball coming. Who had everything planned to the Nth degree and under control.

Phooey on all that.

If you, an imperfect human that you are, aspire to be a great leader, take heart. These idealized leaders don’t exist, except in our collective mythology. Life is messy! Waves of change crash upon our shores all the time, and the best leaders don’t build levees – they surf. They have the confidence to set a bold course and the humility to enlist others to help navigate around the rocks.

“As we look ahead into the next century, leaders will be those who empower others.” – Bill Gates

Because let’s face it: we’re sailing into uncharted waters. Artificial intelligence, the gig economy, remote work, fickle (and vocal) customers… it’s a whole new world out there. The behaviors and traits that set great leaders apart are becoming more about adaptability than about eliminating variability.

“Agile leadership is leaking out from the engineering department and into the C-suite,” says

Michael Cooper, an executive coach who has been working with businesses across tech, law, healthcare, finance for over 15 years. “As a leader, your job is to set the vision, then make sure any trust, alignment, or cooperation issues are resolved in order to pave the way for agility and evolution.”

The bad news is that a culture of trust and adaptability doesn’t just magically appear. The good news is that any leader, whether emerging or executive, can act in a way that creates it.

Great leaders are all about the “and”

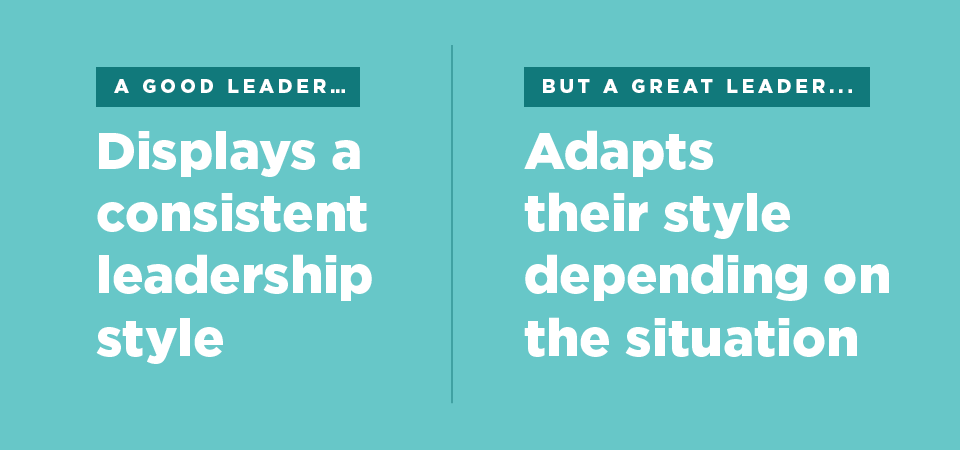

A trap well-intentioned leaders fall into is assuming you have to choose one leadership style or another and project one quality over another – e.g., confidence or humility, candor or diplomacy. Their desire to be consistent comes from the right place, but it’s not necessarily what their team needs.

A great leader can act with confidence and with humility based on what the situation calls for. On a good day, they can embody both at the same time! They provide strong direction to the team member who needs it and give the other team members a lot of room to maneuver. This is the essence of situational leadership.

Winning at the “and” is all about understanding the people you lead, the people you report to, and your peers. If you change just one behavior as a leader, make it this:

- Make time to observe how your team members respond to challenging situations and reflect on whether they most need to be coached, persuaded, directed, or empowered in those moments.

- Anti-pattern: "I treat everyone the same way—harsh but fair."

Great leaders embrace respectful dissent

Wouldn’t it be lovely if everyone in our organizations could align on what the goal should be, and how to achieve it? Building consensus takes real skill and is a hallmark of good leaders. Here’s the thing, though: even when it appears you’ve got 100% alignment, that’s just an illusion. There are always people who disagree but choose not to voice outright. Instead, they’ll find ways to undermine the course of action you’ve chosen – even if unintentionally.

By contrast, great leaders welcome divergent thinking and encourage respectful dissent. The decision-making process looks uglier on the surface and may take longer, but the results are better. The more objections raised and alternatives offered, the more leaders can be confident they’re making a well-informed choice. It’s also easier to get dissenters to “disagree, but commit” (to steal a phrase from Amazon’s Jeff Bezos) when their ideas were heard and considered before the decision was made.

Entertaining diverse opinions is the easy part. The real work here is cultivating an environment where people feel safe expressing dissent. Start by adopting behaviors like these:

- Actively seek out opposing viewpoints, especially from those at different levels of the org chart.

- Encourage team members to challenge the status quo and ask “why?” a lot.

- Respond to criticism of your ideas with curiosity and a willingness to listen. Say “tell me more…” instead of simply defending your position.

- Demonstrate your commitment to making a strategy or tactic successful, even when it wasn’t your preferred option.

- Argue as if you’re right, but listen as if you’re wrong.

- Anti-pattern: "I'm the most senior person here, therefore I'm always right"

Great leaders delegate authority

Think back to a leader you enjoyed working under. Chances are, they were in the habit of deputizing their direct reports with as much decision-making authority as possible. Not only does it free up their neurons to puzzle out higher-level problems, it puts decisions in the hands of the people closest to the work and therefore best qualified to make them.

Another trap many leaders fall into is thinking the weight of making decisions is theirs to bear alone. After all, accountability for a decision’s outcome certainly rests with the leader. (And if you disagree, you need to step out of management. Like, right now.) But as Steve Jobs cautioned, “It doesn’t make sense to hire smart people and then tell them what to do; we hire smart people so they can tell us what to do.”

Leaders who take the time to make sure the group understands why they’re doing something have an easier time loosening their grip on exactly how it gets done. Try these other tactics, too:

- Give people problems to solve instead of tasks to complete.

- Set high-level goals for the team as a whole, then let them decide how to achieve them.

- Let your team know you’ll back them up if they get push-back from stakeholders on a decision.

- Actually back them up. Or, if the decision was so misguided you can’t defend it in good conscience, be sure to defend them as a person, then work with them to find a better option.

- Anti-pattern: “I need you to cc me on all communications about this project.”

Great leaders solicit feedback from their direct reports

Author and executive coach Bill Treasurer describes hubris as the “single most lethal leadership killer.” So when you need a dose of humility, just ask your direct reports how they think you’re doing. This is scary, I know. But if you subscribe to the idea that frequent, candid feedback is the best way to improve one’s job performance, then you might as well hear it directly from the people you’re leading.

It can be uncomfortable for your direct reports as well, though less so if you’ve done a good job fostering a culture of respectful dissent. In her book, Radical Candor, Kim Scott, a former Google executive, advises leaders to ask for feedback verbally, then shut their mouth and count to six. Most people will start talking if for no other reason than to fill the silence. From there, your job is to tease out the ways you can improve. Don’t just let them toss you a few compliments and call it a day.

Use these tips as well:

- Give someone permission to hold the proverbial mirror up to your face when you’re not being the best version of yourself.

- Listen with the intent to understand, not to respond.

- Reward constructive criticism by thanking the other person for their candor. Even (ok: especially) if it was hard to hear.

- Anti-pattern: “You’re just a low-level employee. I know perfectly well how to do my job, thank you very much.”

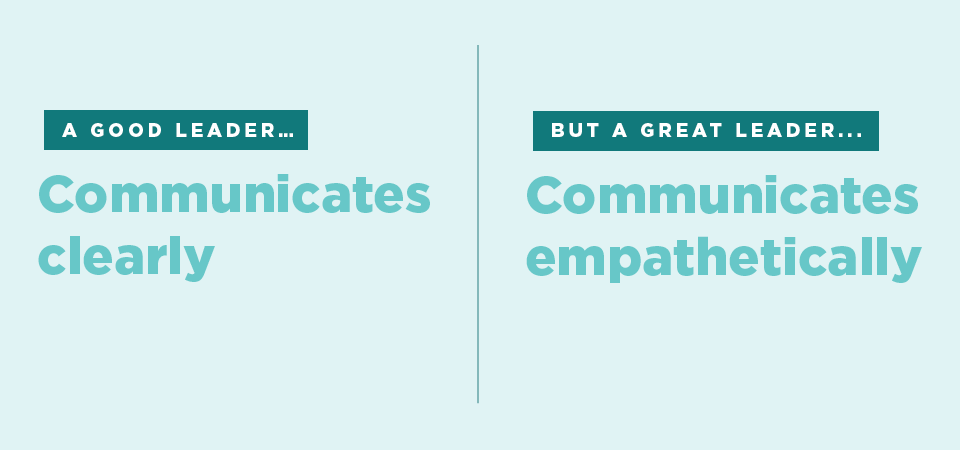

Great leaders communicate empathetically

It’s not enough to communicate clearly. That’s another one for the “table stakes” category. Great leaders understand who they’re speaking to and what the other person needs to hear – not merely what you want to say. This means imagining yourself in their shoes and taking into account all you know about them. Their hopes, fears, daily challenges… the whole picture.

Empathetic communication is especially important when announcing something you know will be controversial or difficult to hear. Our own Mike Cannon-Brookes set an example worth following* when Atlassian decided to sunset Stride, a group chat tool we’d poured a ton of energy into but just wasn’t gaining traction against Slack. He crossed an ocean to deliver the news to the Stride team in person. He praised the product they’d developed and the hard work it took to manifest it. He knew they’d want to know how the decision would affect the future of their jobs and addressed that directly. Hat-tip.

To build your empathetic communication muscle, make these things a habit:

- Practice active listening. Shut your laptop and turn off your phone so you can really tune in.

- Get to know your team members on a personal level to whatever extent possible.

- Try to anticipate the questions or objections you’ll get and address them up front.

- Anti-pattern: “C’mon, buck up. It was just a bit or straight talk… some people can be so bloody sensitive!”

Great leaders are authentic

Emerging leaders are often coached to project optimism and confidence at all times. While this isn’t necessarily bad advice, it’s incomplete. The best leaders convey optimism and confidence when they are genuinely feeling optimistic and confident. For most people with an appetite for leadership, that’s going to be like 80% of the time. It’s what you do the other 20% of the time will set you apart.

Having doubts and making mistakes and feeling discouraged doesn’t make you a bad leader. It just makes you human. Allowing people to see the real you when you’re feeling vulnerable helps build that all-important culture of trust. Say what you will about George W. Bush’s policy choices and leadership in general, but he nailed it on authenticity. He had a checkered past, displayed a questionable command of the English language (“misunderestimated”, anyone?), and people who felt they’d been left behind by picture-perfect politicians adored him for it.

But for the love of Hemingway, don’t go around inventing words like “strategery”. Practice these behaviors instead:

- Set up your desk next to your team members’ and be active in every-day conversations.

- When you mess up, be the first one to point it out and share what you learned from it.

- Be aware of when your personal life is taking a toll on your performance and work, and set an example by being as open as possible about it with your team.

- Anti-pattern: Anti-pattern: “No, seriously: everything is fine. Trust me.”

Great leaders provide guardrails instead of process

Because leaders are on the hook for results, there’s a strong temptation to optimize processes and standardize them across the organization. This is efficient in the short-run, but it comes at the cost of long-term effectiveness because it strips people of their ability to operate autonomously and discourages creative thinking.

For example, let’s say you’re big on continuous improvement. You could mandate monthly team retrospectives using a given format, and that might work well for some of your teams. But what about the teams it doesn’t resonate with? They’ll go through the motions because that’s what you’ve required but won’t get much out of it. Alternatively, you could make sure your teams have time to reflect and adapt on a regular basis, without dictating the cadence or format. They’ll go about it in whatever way works best for them and you’ll get a higher return on the time invested in it.

In practice, choosing guardrails over process looks a lot like delegating authority:

- Leave your inner micromanager at the front door.

- Articulate your expectations in terms of outcomes – not outputs of effort.

- Anti-pattern: “That is how they do agile at Netflix, and by God, that’s exactly how we’re going to do it.”

So, getting back to that trust thing…

Leaders at every level – un-official leaders and influencers, front-line managers, executives – are accountable for creating an environment where people are empowered and excited to do their best work. Building a high-trust organization is a continuous effort peppered with setbacks along the way. The key is having the courage to talk about what’s causing trust issues so you can get on with resolving them.

Cooper, the executive coach, pushes his clients to ask themselves some pretty tough questions. “There are always behavioral patterns underlying these issues,” he says. “Do your people believe you’re acting in their best interest? That you’ll do what you say you will? Have they been disappointed with you or with other leaders in the past?” The answers will guide your next steps.

The future of work holds a lot of unknowns. It’s important to set ourselves and our teams up to be effective and adaptable, even when that doesn’t seem efficient in the moment. In the long-run, you’ll see a big return on that investment. What more could anyone ask of a leader?

This article by Sarah Goff-Dupont originally appeared in Work Life by Atlassian. It is republished with permission.